Summer Gaze by Fiona Beck

Issue 35.4

Editor’s Note

To the Washington College community —

This is, unfathomably (for me, at least), where I step away from Collegian. It’s a goodbye I’ve been dodging. I’ve had my fair share of apprehensions in my time here, but this journal has never been one of them, which makes withdrawing feel like a monumentally impossible hurdle to clear unscathed. From my first nervous submissions as a freshman to these last, insufficient words as a parting note, I have been assured every day, more and more so as they went on, that this is vital work.

I call these words insufficient because a few paragraphs feels microscopically brief to bid my farewell to the thing that’s wholly reinvigorated my love for writing. That reinvigoration is largely thanks to the community I’ve had here, for whom my thanks would consume a journal itself. I’ll do my best to condense it here. Thank you to Justin Nash and MacKenzie Brady, who tugged me headfirst into editorial dialogue, fielded ceaseless questions, and steadied me at my most frenzied. Thank you to Emma Campbell and Eylie Sasajima, who showed me that being an editor in chief is an endeavor of patience and care. Thank you to the editorial boards of volumes 33 and 34; a good team is rare, but I’ve gotten to be on three. Thank you to Dr. James Allen Hall for many things, but prominently: bringing me to Washington College; meeting my (many) frantic emails with reassurance and insight; and being a stabilizing advocate for student writers, artists, and editors.

Most invaluably: thank you to my staggeringly brilliant team. I’ve been privileged beyond belief to have the editorial board that I’ve had. Caryl, Joshua, Lucy, Vee, Seth, Sophia, and Iris are the very best group I could’ve asked for. I came to this position with lofty ideas, and the seven of them exceeded even my most out-of-reach ambitions. I am thankful to them each for their dedication, enthusiasm, ideas, constancy, and friendship. Lucy will be picking up where I leave off this year; she is a discerning editor and a tactful writer, but more than that, she is a compassionate leader and a thoughtful person. The former traits mean nothing in an editor in chief if they are not braced by the latter. I could go on, but I’ll let her tenure prove my points for me. Volume 36, I’m certain, will be exceptional.

Perhaps appropriately, this final issue of volume 35 is one of rebirth. Our writers and artists built dream states, blazingly bright scenes, and astute depictions of hope. I trust you will feel this — be gripped and eased by it — from start to finish. This issue is fresh fruit, young blooms, and impossible sun. It’s a note I’m proud to end my editorship on. I joke that Collegian is more my thesis than my actual SCE, but there is some truth to that. When people ask about my undergraduate work, I will direct them here first. Thank you for reading.

Be good to one another,

Sophie Foster

Editor in Chief

Table of Contents

“Into Infinity” by Rae Merson

death of ziggy! by Ziggy Angelos

“Follow Suit” by Julia Stanley

“How to Embroider a Pair of Thrifted Jeans” by Jaya S. Basu

I by Isabel McCreary

“Restoring the Meadow” by Grace Hogsten

Spore Print by Morgan Carlson

“Coniferous Pink” by Jaya S. Basu

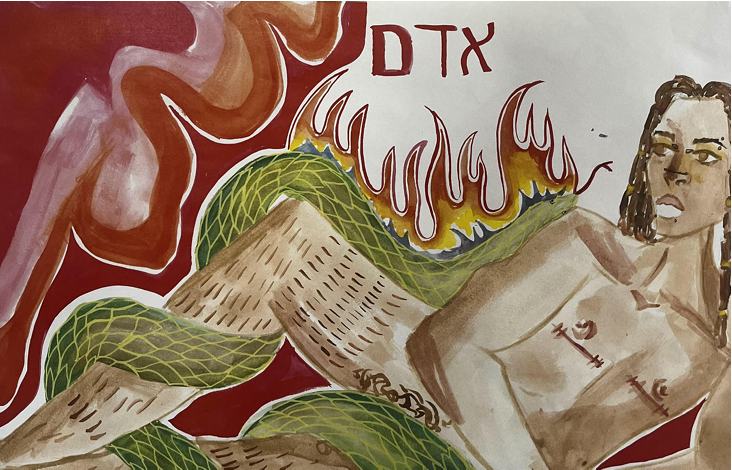

My Adam, My Eve by Ziggy Angelos

“Smack of Flesh” by Jaya S. Basu

“Super Fruit” by Ziggy Angelos

Sudz by Fiona Beck

“It Will Begin” by Sheri Swayne

“Star Tipping” by Grace Hogsten

“Become What They Make You” by Amelia Watson

III Growth by Ella Humphreys

“Bonfires (Ash Becomes Them)” by Connor Cordwell

by Rae Merson

Into Infinity

I don’t know if you felt it, but there was a rise of existential dread this summer.

Centrally located in the first state, trepidation washed upon the blacktop of my neighborhood. I had such high hopes for the warm season: a promising internship and new love lined up for me. Opportunities which my previous nihilism never thought possible — opportunities which I quickly discovered were not always that ideal.

As the days marched on, the wave of dread crept closer.

It was a wave I rode shortly before I reached out to my doctor, who finally decided that having endless rebounds of major depressive disorder was enough for me to qualify for the little check next to the box labeled “chronic.” I got a new pill to take, a new disorder to add to my growing collection. It was one that I had sworn I would outrun, but there’s my luck I suppose.

I remember adding that pill to the others. There were so many now. I am always fluctuating between how many little capsules must go in my system. Seven. Fourteen. Two.

God, I remember when it was just two.

But that pill was the crash. It was the foam on the shore that would lead me to recovery and solid land. The wave itself, with its roaring waters and treacherous peaks, was a murky abyss I had to first traverse through.

Every night that summer, even when work was there waiting for me the next day, I would spend hours watching nonsense. Movies, TV shows, documentaries — endless static to distract my torturous mind, to fill myself with affection and thoughts that I craved from another. I saturated my brain with countless ways to make my body numb, to not have to comprehend what was going on in my life.

Work was fine. In fact, it was delightful. It was having to look at myself in the mirror. Having to look at what I allowed myself to become. Allowed myself to decay into.

Send another picture.

My phone would buzz near constantly. I hated him, but I loved him too. He was the first person I had let back into my life in such an intimate way after I had vowed to keep all harm away from myself. My body was a temple, or so I was told, and I thought he understood that. I thought that after all I had shared, he would keep me safe.

Let me see you.

I hated it all. I hated that I let myself think that this was the only thing I deserved. That without him, without his version of love, I would be destitute. His words suspended me into a void of liminality, simultaneously thrust between his current torment and the haunting wounds of past. Past hands — past faces — past voices. I wanted to crawl out of my skin, let it soak in cleansing waters and air dry in the backyard. But no matter how many times I rinsed and rinsed, I would never be clean enough to wear myself again.

Flashes of the past would ebb into my mind, their constant reminders of what mistakes I made or what actions I should have taken crawling around my mind. They were maggots at a rancid feast eating upon my sanity, forcing me to reflect on how I got to where I was.

I often silenced my phone when it got to be too much.

Locked away in my room, projector aimed at the ceiling, I would lose hours in my isolation chamber. The near constant cycle of self-loathing and gorging myself on static ended up with me watching space documentaries.

Space and time. Time and space.

At first, I was horrified with how small I was compared to everything. How it confirmed that I didn’t matter. How everything just… continued and was the same yet ever changing and…

…and I eventually discovered that with Infinity there were infinite possibilities of Me — and in that infinite void was where I could finally choose.

I saw, by watching those shapes and colors swirling above me, that the state of human beings is so much more than what we think we are. We’ve advanced to see the universe and understand what we are on a particle level. We can see the limits of creation itself. We can fit incomprehensible waves of data into little discs we could swallow. Worlds of information, trapped in nothing larger than the tip of our pinky. We can tap into a different wave of dimension and put music and color and sound though it. We can transform and be transformed. We are ever changing and ever being changed.

If we could do all that, what was stopping me from doing the same?

Something erupted within me, a supernova of years of pent-up anger. Reserves of heat that had built up in the nucleus of my being. For the first time in my life, a boiling point of rage on my own behalf had been reached. Much like a star’s own birth, a rejuvenated version of myself had been born.

The core was ecstatic to get to work, constantly bursting with energy and desire to step forward into the emerging light that was me. But the shadows that remained of my past, the terrors that continued to plague my system, needed addressing.

He needed addressing.

I knew I had the power to undo the ties that bound us together. A separation of particles that were never meant to be together severed with a firm ‘no’ that I had never known I could use. A hard conversation. A block. A motivation sparked by a cosmic metamorphosis.

Matter cannot be created nor destroyed — it can only be changed.

My matter — my very being — was in a state of change. Some points had already begun their transformations, morphing from mere dust to stars that hung around me. No longer mites that bit my ankles, but rather lessons learned and refined into new irreversible aspects of my soul. The projections of others that I once saw as permanent, disfiguring scars were now the very constellations that painted my essence.

But the present — the current wave that felt never ending — was starting to become a tangible project to me. Effort into myself, into preserving my body and life and presence was no longer some daunting mission only the universe could handle. If we could be anything, then so could I.

Life was not over, certainly not when it could continuously change itself in such magnificent ways. Out there, beyond even our conceptions, lays the opportunity for infinity. And in there, projected onto my bedroom ceiling I saw not only into that infinity:

I saw hope.

death of ziggy! by Ziggy Angelos

by Julia Stanley

Follow Suit

A man in a suit is a frequent visitor to my dreams. We meet often. Different places, different times. Same man, same fear.

I have never met him with open eyes. He lives in my head, although I feel like a visitor in his. I know nothing of him but the game we play.

A game of cat and mouse. Last month we met in a house on the cliffs in Malibu. Open concept and daunting glass windows, nowhere to hide. Two weeks ago, an apartment building. High ceilings, marble floors, and plenty of little hallways and crevices to duck into. I have played this game with him across the world, across time, across universes.

I always lose.

By now, I understand the way this works. I see him. I run. He follows, an army of his men on my tail, all dressed in the same dubiously drab charcoal gray suit and navy tie as him. Turning corners so sharply I almost wipe out, taking the stairs three at a time. Hiding in a janitor's closet next to bottles of bleach, the scent stinging my nose. Closing myself into a wardrobe, tucked behind lacy ballgowns and cashmere sweaters. Doing anything I can to hide myself from his piercing stare and the snatching hands of his lackeys.

I will make the mistake of darting out into the open in search of another way out. He will notice every time. We have met on the deck of a ship, in the lobby of an office building, on a train car. He will always find me. We will always meet again.

I’ll make a wrong turn, take a break, try to hide away in a crowd. But he has too many allies. He has the past, present, and future on his side.

He has a frown painted on, some twisted semblance of care in the way he looks at me, looks through me. His silver hair is bright, the distinct swoop of his cowlick is the same in every dream no matter the situation, the place, the chase.

I’ll turn and run, ready for the chase to begin again. One step, three yards, my hand on the doorknob, my worn-down shoes slipping against the tile.

He’ll shout. The words don’t matter, they never have.

I’ll turn on my heel, find his eyes, and run right into his arms.

The last time we met in my dreams, I was wearing my green bandana. His arms caged me in a delicate hug, he pet my head, and I just barely felt his index finger brush my hair back.

I haven’t worn my green bandana since.

by Jaya S. Basu

How to Embroider a Pair of Thrifted Jeans

1

Measure out a length of embroidery floss about half an arm span long.

Finger your thread snips until you slice up the delicate flesh of your fingertips.

Remember that your fingers are not delicate. They are calloused from years of hand sewing.

Recall the first shirt you made. You hand sewed it—too ashamed to admit you broke your grandmother’s machine but too stubborn to give up.

Snip out what you need—no more, no less. Regulate the length like you regulate your volume, your tone, your hunger, your laugh, your calorie intake, your ecstasy, your ibuprofen, your love.

Think about taking ibuprofen. Decide not to.

Close your lips around the fraying end and lick the fibers down like you are ravenous.

2

Pinch your fingers around the end until you can’t see it anymore.

Pick up your needle. Name her Veronica. She is cold and thin, like your first girlfriend. Kiss her. Hope no one saw that.

Jab the end of your thumb to make sure it is sharp enough. Use it even if it isn’t.

Roll its length between your thumb, index and middle finger to feel if it’s bent. Use it even if it is.

Pass the eye of the needle down the crack between your smooth calloused fingers until you feel the thread has split, half in the hole and half outside. Repeat until it isn’t.

3

Wrap the other end of your thread around your index finger and pass the end through the loop that it forms.

Pull the knot tight. Tight as you hold yourself, sucking in your stomach when you tuck in your shirt. Make sure no edges are sticking out of the top of your pants. Pull your shirt down taut. Tighten your belt by one notch and tuck the end in your front left belt loop. Smooth the cowlicks in your hair with clean-smelling pomade. Try again when they stick back up. Try again when they stick up after that. Give up. Wear a hat.

Trim the end. Trim your hair. Trim the fat. Trim your laugh when it’s too loud. Trim your voice when it’s too high. Trim your friend group when you all decide you don’t want her there. Trim yourself when your friends decide they don’t want you there.

4

Grasp the needle with thumb, index and middle finger. Hold it tight enough that it pierces thick canvas. Do not hold it so tight it bends. Do not hold it so tight it snaps. Do not hold it so loose it slips away. Do not hold it so loose you forget how to hold anything ever again.

Let the needle slip through your fingers. You forgot.

5

Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce the fabric. Pierce.

6

Kiss the bruised purple of your middle finger.

Suck on the red pad of your thumb.

Nibble the white scab forming on your index finger.

Thank the needle for the pain.

7

Wash the blood out with hydrogen peroxide. Sell the piece to a stranger on Etsy.

I by Isabel McCreary

by Grace Hogsten

Restoring the Meadow

Under well-intentioned guidance,

I made the meadow that was my body

a neat and tidy garden plot.

I laid the land bare, uprooted

wildflowers and native grasses,

those things I loved that nourished the soil,

in favor of aesthetics.

Weeding delivered pretty rows

lined by empty, brittle dirt.

I surveyed my work,

aching and weary,

and saw only land depleted.

Now I burn away every trace

of curated perfection, leaving

only soil, with which it all began.

I replenish squandered nutrients,

let the grass go to seed,

replant, all so my meadow

can bloom again.

Spore Print by Morgan Carlson

by Jaya S. Basu

Coniferous Pink

i.

The wind whimpers, her

magnolia-petal breath sweeping

the silent landscape and

barren alleys. She brushes her rosy

fingertips along the

reinforced steel plating, speckled with

rust and pigeon shit.

The water coughs,

sputtering on dead leaves and cigarette butts.

Carbon compounds snake around her throat;

a sixfold yoke, a deadly diamond necklace.

ii.

The God who has never shown his moony face,

and doesn’t intend to, is

there. He hides

on the leeside of the mountain,

cowering in the grotto

he constructed for Himself, a

cavernous mouth with stalagmite teeth,

walled with clay and silicone.

His cells have

dissipated. They have dispersed

into the suburbs and concrete

and glass, where they

root in crevices between grout-smeared

cinder blocks and

dissolve.

Our calls go unanswered,

pinging against His ice-capped skull, as we

ask and ponder and pace

the linoleum halls and

mossy clearings. If He

has an answer, it is not written

on His wrists; the blue-but-browning rivulets against

ashy earthen skin spell out no new revelations

or unfalse prophecies,

just a promise that He loves and has not left us.

His love is not enough to cool the fall.

iii.

The lab is overgrown,

grass sprouting from in between

the cracks in the floor tiles. The scientists

miss the days when the wind sang.

Her music reverberated

down mountains and up rivers,

plunging into eddies like

twirling, pinkless ballerinas.

The researchers must bear knowing: the truth

is shocking and coniferous.

My Adam, My Eve by Ziggy Angelos

by Jaya S. Basu

Smack of Flesh

Flesh tastes like veal. You know this. Others have heard it, maybe read it online, but you know. It smacks against pavement like bursting water balloons. The early morning dew smells like sweat—salty and unquestionably human.

They’re naked when they come down. You wish they weren’t—you don’t like looking at flabby genitals or rolling hills of fat or birthmarks in places you never wanted to see. You’ve always been uncomfortable and embarrassed with nakedness—most people are, you figure. But you’re different. Your discomfort is crawling, snaking, engrossing. Your shame is licking, seizing, all-consuming. Still, you look. You hate that you look. Disgusted as you are, you cannot stop looking.

You restrain a gag as one thumps to the grass before you. Your porch is covered, so you are safe as you sit on the porch swing and sip your coffee, looking out on your dew- and corpse-covered lawn. The bodies fall in uneven spurts like hesitant spring rainfall. Now a few, then a pause, then a few more. A cacophony of thwaps echoes down the street against the red brick and wood-paneled homes. Some of them lie rigidly spread-eagle, stiff from rigor mortis, atop hills of tissue, while others flop down into valleys of skin. Skin surrounds you: freckled skin, wrinkled skin, dimpled skin, ashy skin. Your own skin starts to crawl. You avert your eyes and finish your coffee.

Except you can’t avert your eyes, can you? There is no space to avert your eyes to that isn’t occupied by another body. Bodies, bodies, bodies, everywhere you look, covering your lawn, the road, neighbors’ roofs, your car, trees, your deck, looped through the tire of the tree swing down the road, filling the hole in the excavator site that was supposed to become a new split-level, leaned against the door to the shed where you keep your rake and snow shovel. Your neighbors are also on their porches. Some with children, some also sipping coffee, some watching each other, some watching you.

The neighbors know about your perversion. Your deviancy. Everyone does. You’ve had it since you were a child. You were seven years old when you first hungered and fourteen years old when you started hiding it. It disgusts you. It revolts you. The others concur—you are disgusting. You are perverted. You are broken. You find reassurance in their words. It soothes you to know that your revulsion at yourself is justified. It is hard work to hate yourself as much as you do, but you do it gladly and tirelessly. If you can’t stop yourself, at least you can hate yourself.

You run your tongue over your teeth. The bodies continue to fall. They smack, they thump, they thud, they splat. You cannot look away from them. Your neighbors cannot look away from you, looking at you looking. It is the looking that hurts. Not the biting, or the tearing, or the feeling of flesh relenting, ripping, ravaging under your teeth, but the looking. The perversion is looking. The deviancy is noticing. You notice the sword tattoo on her upper thigh. You notice the long, jagged stretch marks racing up his right hip. You notice the way fat piles in doughy rolls, the way cellulite jiggles on impact with the ground, the way flesh sags, depresses, deflates, drifts. You notice the way your fingernails have started to drum against the side of your mug.

Your eyes are wandering fingers you cannot still, poking and probing like they’re performing an autopsy. You shove them in pockets and you set mouse traps to snap at them and you stuff them as far as they will go into your mouth, but you cannot stop the way they roam the bodies that litter the streets. The bodies stack and slide off of the ones before them, collecting in massive heaps. You listen to the bodies thumping against the roof above you. Slowly, you finish your coffee and press your fingers against the still-warm mug, savoring the respite from the chilly morning. It is early, you are tired, and you are hungry.

Involuntarily, you lick your lips. Across the street, a father pulls his child closer to him.

by Ziggy Angelos

Super Fruit

My life-changing,

soul-ruling,

dare-deviling,

sustainable,

reusable,

artisanal

diet.

It takes one second to crunch a pomegranate whole.

Pop and juice and maroon and magenta and and and—

once you devour and conquer the seed—

wave a gentle hello to the pokes and prods from your lower psyche awakened in a bubbled irritability.

Another please! Lemon water to wash down the needing…

I want a love to break me!

Pomegranate: pomegranate?

I want a fruit to change me?

Pomegranate: pomegranate!

There is no good found in

kitchen scissors,

no god in the oven, nor the drippy sink,

no higher power in my carrots, my trash pail,

no buddha in my spatula.

Pomegranate: pomegranate.

Supple and needed and engorged and engulfed, broken into one thousand four hundred drops of sweetness,

enough to go around.

Super fruit.

My fridge is full of

fickle unbelievers,

unfeeling fellows,

neglected half-eaten treasures.

And there you are giving home to the grief.

My fridge is full of pomegranates, and I am never full!

And I am never full,

And I am never full…

My monetary discrepancy,

eternal divine wail,

involuntary satisfaction,

palms raised up,

my brimful mug,

I sway to my super fruit.

I sway. Devour,

wrapped in apron…

I sway. Devoured—I sway.

Sudz by Fiona Beck

by Sheri Swayne

It Will Begin

It will begin when they are about to leave. He will see straps and beads and powder. He will see her put on her shoes. He will see her lips move to ask if he’s ready. He will watch her float about the guests. When she smiles, he will feel it in his cheeks. When she laughs, he will feel it in his chest. When she walks, he will feel it in his throat. He will watch her, and think of bathroom stalls, of hallway walls, of empty rooms. He will catch her eye. She will walk to him. She will pull him down and whisper something—he will not hear what it was. He will breathe in her perfume. His eyes will close. Her arm will wrap around his and he will close them tighter. He will open his eyes and watch her lips. She will say she’s ready to leave. He will lead her to the car. He will keep his eyes on the road only. He will hold the door for her into the house. He will hold her gaze, read it over and over. He will imagine what to do first. He will feel it here and here and there. He will take off his jacket. She will suck in a breath. And it will begin.

by Grace Hogsten

Star Tipping

It’s a crisp October evening, a Wednesday, and you’re thrilled to be out and about on a school night. For the first time, your mother is bringing you along to one of the Pampered Chef parties her friends-of-friends host a few times a year. The neighborhood mothers spend the months in between parties waiting for the next excuse to chat about husbands and children and page through catalogues. Tonight, you get to join them.

Over a low-fat charcuterie board and a platter of fruit, the woman hosting the party talks about how she’s climbing up the ranks and soon she’ll be supplementing her family’s income just by selling cookware out of her living room. She won’t. Nobody really can.

But you don’t know this yet—you’re only thirteen and along for the ride.

You sit on the piano bench at one end of the living room with your back straight and your chin up. You’d lean on the piano, but you’re not sure if the keys are exposed and don’t want to risk the noise. In your peripheral vision, you can see the host’s son Henry, a boy from your class, leaning idly against the doorframe and taking in the party from afar. Next to him, his younger sisters, ages seven and five, sit restlessly on wooden chairs dragged in from the kitchen. The host starts talking about the one-pot meal she made in her new Dutch oven.

“Your children will love it,” she says, looking over at Henry.

“If you fix it up first thing in the morning,” says the mother of a girl on your bus, “it’ll be done simmering by the time your husband gets home from work.”

You nod and look attentive; you’re trying to shift your image from “sweet little girl” to “lovely young woman,” and so far, it seems to be working. You try to focus on the woman at the front of the room, but your attention drifts each time one of the little girls shifts in her seat. When the host brings out a new nonstick pan to show off, Henry leans over and whispers something to his sisters, who stand quietly and slip out the door. He takes a step backward into the hall, motioning for you with a small wave of his hand, and you turn involuntarily. You know he wants you to go with him.

You look back at the nonstick pan and resume your upright posture, but a second later you’re standing up. You leave the piano bench and the talking mothers behind, following Henry through the hall, into the kitchen, and out the back door.

A porch light illuminates the yard just enough, and the cold feels refreshing against your warm face. You hadn’t realized how stuffy it was inside. The air pricks your skin and seeps through you—it’s exhilarating.

The little girls run to the swings while you and Henry stand on the steps. You’ve never been to his house before; to you, he’s someone who exists against the backdrop of a classroom or a cafeteria. He leads you to the chicken coop to show off his pets. The four hens have bedded down for the night, but he opens their tiny wooden door and the boldest pokes her head out right away. Henry picks her up.

“Want to hold her?” he asks, already placing the chicken in your arms.

She’s so warm and much softer than you expected. You feel her downy feathers brushing your forearm and watch her head move as she looks around the yard. Henry tells you about how he and his father built the chicken coop last summer and how he’s been feeding the hens each morning since they hatched. The chicken in your arms adjusts her position, and you hold on until she pulls her wings free and starts to flap them. She lands on the ground in a flutter, and you and Henry laugh as she marches away.

Eventually, the little girls drift over and the conversation lulls.

“I know what we should do,” Henry says. “Let’s play star tipping.” He explains the simple game: look up and find a star, then spin around twenty times and try to walk across the yard.

You volunteer to go first and feel a flutter in your stomach when he grins.

Henry runs to the steps and switches off the porch light. Stepping into the center of the shadowy backyard, you tilt your face skyward and set your sights on the brightest star in Orion’s belt. Henry and his sisters form a wide circle around you, so you won’t stumble into the house or the fence and you only have to think about the stars.

You spin and spin and spin and the constellations blur into a hazy glow. Henry shouts to stop at the count of twenty and you fall to the ground before you can take a single step. You can’t stop laughing, and the little girls laugh too. Henry leans over to help you up and you try to stand, feeling shaky and giddy while you look at his face bathed in warm light from the kitchen windows. You drop his hand and ease back down, not ready to hold yourself upright just yet. The stars slow their spinning and shine independently once more.

“What are you doing?” Henry asks, and you don’t have an answer.

You just want a moment to look at the stars.

by Amelia Watson

Become What They Make You

My father used to say I moved too slowly,

That I walked as though wading through molasses,

The syrup trailing my feet

Like an unforgiving shadow.

A gnawing, pulsing in the gums

As the molasses sticks to the tips of my wandering teeth;

Moss-stained stalactites and stalagmites

Never quite aligned,

Jagged white bones

Begging for absolution in their imperfection—

Is perfection a thing to be strived for,

Or a thing to run from with animal apprehension?

This world is too fast for me, too perfect.

Never-ending movement:

The slow drag of the hour

Against the quick ticking of the clock.

A late train that somehow, impossibly,

Always reaches its destination on time.

I can hold a petal in my bruised palm, knowing it will die,

And enjoy it as it withers without letting go too soon.

You can slow down too;

I will show you how.

You will need some molasses

And some crooked teeth.

III Growth by Ella Humphreys

by Connor Cordwell

Bonfires (Ash Becomes Them)

Once the grass again

grows greener, will you notice

its scratching on your skin?

When the pines start to flourish,

won’t you feel each needle

stabbing at your soles?

Friend, you were always

the type to wear shoes.

But you will see yourself,

this time, in every falling

bloom. And when the leaves

begin to rot,

you’ll swear

you can still taste smoke

on your tongue.

Born anew,

will you look to summer's old dog

and place yourself in his rusted jowls?

And in his withered eyes

you’d see stars,

dimmed, but ever brilliant.

And, though decay

is ever extant,

life persists.

Take your shoes off,

lover, we go on.