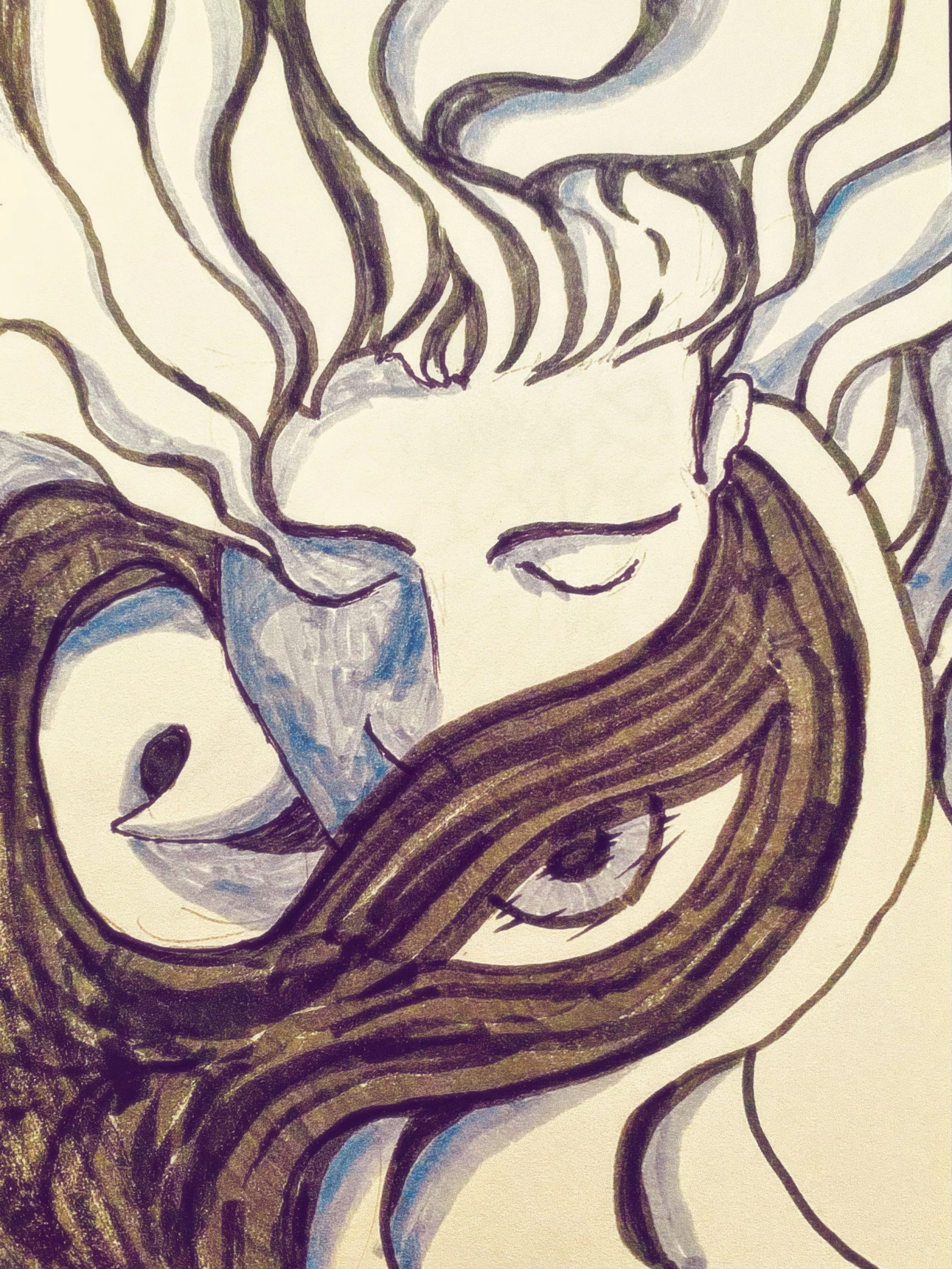

Strange Embrace by Jeremy Cress

Issue 37.2

Editor’s Note

Dear Washington College Community—

After all of the exams, quizzes, papers, deadlines, group projects, and advisor-meetings to ensure a timely graduation and to avoid impending doom last semester, I’m sure you’ll realize that these colder weeks and months aren’t all that bad. Maybe you’ll suddenly be walking in a store and be dazzled by all of its Christmas and New Year’s marketing and decor and suddenly snap out of your academic stupor and realize you’re standing right in the middle of the season of joy and generosity. I think it’s safe for me to say that the root of each of these fundamental elements is people. People are magic. People have the capacity to remind you that you are fun to spend time with and you can laugh so hard your breath leaves you and you are funny and intelligent and social and considerate and tragically unserious and beautifully complicated. People remind us we’re real. So people, open up issue two of Collegian 37 and experience the real.

As always, and despite the holiday charm, the real is hard. People are hard. However, writers and artists have the ability to observe, devour, and transform (not explicitly in that order) the hardship into something tangible and relatable. Writers and artists are exceptionally talented at wrestling with people on the page or canvas or through a camera or paper. Is this avoidance? Confrontation? Who knows? What is art if its interpretation isn’t a little challenging? I invite you, then, reader, to interpret how this issue’s contributors wrestle with the habits and hardships of people, whether real or imagined, created or observed. I guarantee one of the poems or artworks or stories is going to remind you of the people in your life that you either think about all the time and miss dearly or those you want to reconnect with. Just as this issue’s contributors have written and captured their experiences and imaginings of people and truly wrestled with them, after reading, I hope you find a similar courage and wrestle with those in your life that have wrestled with you. Maybe wrap a gift and drink some hot chocolate while you’re at it, though.

With love,

Sheri Swayne

Editor in Chief of Collegian

Table of Contents

“we the people” by Solomon Bradley

Mama in the Kitchen by Isabel McCreary

“Wallpaper” by Maria McGinnity

“Good Grief” by Evelyn Lee Lucado

Skipping through Scarborough by Julianna Nelson-Gaudette

“The Same Schedule as the Stars” by Evan Iseli

District Lamb by Julianna Nelson-Gaudette

“Handbook, for Pressing Flora” by Melinda Kern

On the Chester River by Isabel McCreary,

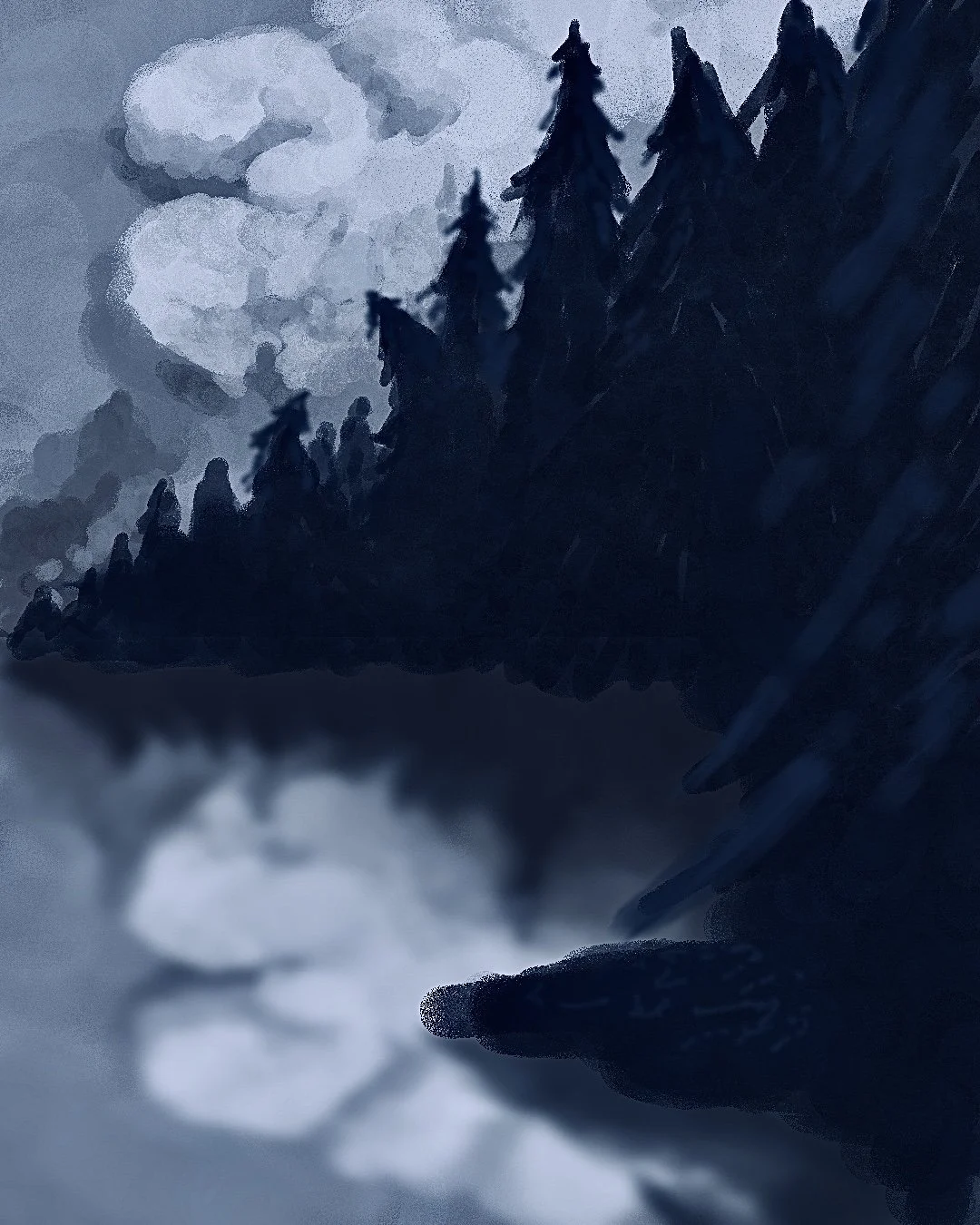

The Silent Choir by Jeremy Cress

“A Talk with Anubis” by Solomon Bradley

“Hero” by Sarabeth Metzger

“Between Two Deaths” by Melinda Kern

Draco Mortem by Jeremy Cress

by Solomon Bradley

we the people

After Gwendolyn Brooks

Real America done gave me a face full of hot freckles, left the rest of me

Cool to the touch, and

We the people dont care.

Left out to rust, the radiofields screech about them baby-killing commies — in

School today they showed us cartoon drawings of a fetus all cut up, so

We the people dont think of the mother.

Lurk round here an you really gone git fucked, fag says mr davis

Late stays aint always end well fir your type says ms josie

We the people laugh with them at church.

Strike three and youre out, darlin. now you best tell me

Straight — did you stain pop pops robe?

We the people get hit anyway.

Sing in the choir every sunday like father gunn said, and as the lord is my witness, your

Sin gonna completely disappear. dont matter what ya did.

We the people hope hes telling the truth.

Thin pot-smoking lazy immigrants and soot-faced thugs drunk on

Gin run wild in the big city. i hear one shot uncle billy.

We the people aint paid to fact check.

Jazz aint allowed when we go to see nana and pop pop every

June — they say its monkey music but i aint understand.

We the people pretend its just a joke.

Die in the middle of the walmart, and wont nothin in this town change

Soon our votes gone kill us all and we still gone play victim

Mama in the Kitchen by Isabel McCreary

by Maria McGinnity

Wallpaper

Even when I felt nothing, I hated my father. My mother too, but hating her was like hating myself, so I don’t like to dwell on that more than I already have. I saw myself as the wallpaper in my childhood home. Technically a part of the house, but nothing important, nothing to consider much beyond knowing that it would always be there. That was my father’s problem—he took me for granted. Every day he would pass me, sometimes scrape up against me, but never worry about the marks he left.

I think I hate my mother because we are so similar. I think I blame her for shaping me into the person I am. She simply filled in the sliver of space that my father left for her. I envied her for having his shape to mold around, for leaving me with no form to cling to except the walls he owned.

Seeking a shape outside of my house was never an option. At school, I was invisible. No one ever brushed against me or cared that I was there at all. My appearance didn’t help. Pale blond hair hung lank, hiding my blank face. Shapeless sweatshirts were my clothing of choice. I had gray eyes, or maybe blue, but no one cared enough to tell me which.

At graduation, I was surprised when they called my name. Sometimes I almost forgot it. I was not surprised by the lack of cheering; I had not expected my parents to come. When I got home, my mother was gone. My father sat at his desk, noisily chewing his BLT, the same sandwich my mother made for his lunch every day. As I came in, he kicked his shoes off and they hit the wall, leaving black scuff marks. He did not look at me, but continued typing on his computer, his overgrown nails clacking against the keyboard.

I asked where to find my mother, but he did not reply. I stood there for a moment longer, listening to him chew and type. Then I returned to my room. The house felt the same, yet I knew everything was different. Initially, I tried to convince myself that I was overreacting—he must have sent her on an errand for him. I tried to ignore the twisting in my gut and avoid thinking about it. It was not important, that’s what my father would have said.

The next day at lunchtime, I smelled bacon and ran downstairs, expecting to see my mother by the stove, carefully checking to see if the meat’s color was just right. It was a sight I’d seen daily for as long as I could remember—my mother hunched over the frying pan, the vertebrae in her neck visible beneath her thin skin, hair tied in a neat, pale blond knot atop her head. But the broad shoulders were not hers; she would not have let the grease spit so loudly, not when it could distract my father from typing. My father was not typing that day; he was frying the bacon.

Silently, I crept back up to my room. My mind ran anxious circles around the topic, crafting possible explanations. She had been at the house when I left for my graduation, but sometime during the hour I was out, she had left. I pictured her neat bun bobbing as she marched down the road by our house, threadbare suitcase in hand. It had been my graduation day—the official day she had finished her job of raising her only daughter. The day she completed her duty to my father of ushering his child into adulthood. Perhaps that was all he had required from her before allowing her to leave and discover her own shape. And if she had left, maybe I could too.

Hours flowed by like honey as I considered my own possibilities. I had rarely thought of my future, but when I imagined myself, I always pictured myself in some faceless man’s kitchen, flipping bacon, my hair knotted practically above the vertebrae that were visible through my skin. Perhaps I even had a wallpaper daughter of my own. It wasn’t that I enjoyed my life, but it was all I knew and all I expected.

I could leave myself in this room alone—I could do that. I could grab my own briefcase and follow her footsteps down the dirt road and along the street beyond it. Why shouldn’t I? What was there here for me besides fixing my father’s lunch?

So, I gathered all the money that I had saved from my grocery store cashier job and packed a bag. In it, I put only the necessities: one hundred dollars, a few pairs of clothes, a loaf of bread and the cold leftover bacon. If I was going to restart my life, I wanted to do it right: from the wallpaper-up. My heart thumped in my chest as I descended the stairs and opened the front door. I held my breath for the sound of my father’s voice, but I heard nothing. Once my feet reached the pavement, I fled.

I had no friends to turn to but Wanda, an older co-worker at the grocery store who had always been kind to me. Two days later, at work, she pulled me aside and asked me (in a tone my father would call condescending) if I had showered recently. Her eyes sparkled with concern that I had never seen before in my own mother’s face. So, I told her what she needed to know. She offered me the basement of her home, offering me a place to stay until I got back on my feet.

The first man came straight out of my expectations. His name was David, and I ran into him at the grocery store where I worked, about two months after escaping from my childhood house. My days were full of nothing but scanning groceries, and his dark eyes were a welcome distraction. Wanda smiled encouragingly at me as he flirted over the potatoes I scanned. Objectively, everything about him was right. He looked like my father: with broad shoulders and dark eyes with a hungry glaze in them. It was odd to see the hunger directed at me; I felt closer to my mother than I had in months. He asked me out as soon as the potatoes reached the cart.

My first date was dinner at the local Italian restaurant, directly after my shift. David went home to put his groceries away and came back to pick me up. I liked that he was punctual and that I could talk to him. I liked that he saw me, despite the translucent skin that had slowly been thickening with every day that I passed divorced from the wallpaper.

I talked a little—about my job at the store, about my age and name and the high school I had just graduated from. David talked a lot—about his job at a construction company, about his age and name and the college he had just graduated from. Despite my feeble protests, he paid the bill. His calloused hand guided me by the small of my back to his car. The drive home was long and quiet, just like the ones I tolerated with my parents as a child.

When David drove away, I watched his taillights disappear into the distance until they were a distant glow I could blink away. Even after one night, I knew a life with him would be safe and familiar. It would be what I had always expected for myself, but it was not what I wanted. The next day, when David came into the grocery store, I hid behind the tampon display until he left.

I only had to repeat this three times before he got the idea. The last time, he saw me. We made eye contact through a slit between the flowery pink boxes. His dark eyes narrowed, the hunger fading to a cold darkness. You’re not who I thought you were, they said. In response, I lifted my chin: I don’t think I am.

The second man sold me red hair dye. Two months had passed since I had seen David, and I was ready for an outward change to reflect the inward one I desired. This time I was the one to initiate the flirting, smirking and pushing out my chest, recreating the mannerisms of sexy girls who I ran into at my co-worker’s parties. It was surprisingly easy to slip into someone else’s skin—maybe it helped that my own was so translucent.

The boy’s name was Ryland, and he acted as much like my father as I did my mother. Ryland blushed at my flirting; he was shy, endearingly so. Big blue eyes avoided my bold eye contact, but his flushed cheeks betrayed his true feelings. I asked him out as my bag of hair dye reached my hands. I asked him if he wanted to dye my hair for me and he stammered, why not. At his place, I insisted, because I knew I would be myself in my co-worker's basement.

Within moments of crossing the threshold of his apartment, I kissed him. In my new sultry skin, it was fluid and seamless. My hand pressed against his neck, fingers stroking down the vertebrae of his spine, claiming them to be mine. I moved his hand to my waist, which was bare below the neon sports bra I wore.

It wasn’t my first kiss after all, at least not when I was in that skin. Chuckling into Ryland’s surprised gasp, I pressed myself against him and took what I wanted. It was a powerful feeling to be the one who took, the one who saw, the one who had control of the situation. I only gave him permission to take a break so that he could dye my hair. After all, wasn’t that what I had come for?

When he finished, he handed me the mirror and asked my opinion. His eyes clearly communicated what he thought and that mattered more than I wished it had. The vivid scarlet stood out against my fair skin, my eyes dark, intense, and hungry. My father’s eyes. The thought came suddenly, and I almost dropped the mirror. I kissed Ryland for a few more weeks to chase the thought away but I saw my father’s eyes every time I looked in the mirror.

As soon as my roots began to show, I decided it was time to move on from both Ryland and the red hair. Every time I saw Ryland’s big eyes and translucent skin, I saw my mother. And who else could that make me but my father?

At a different store, I bought a box of dye that was the closest to my natural shade. Then I went back and exchanged it for the brightest color I could find, a deep violet that could not be ignored. As I washed out the red, it spread in the tub like blood, like the remains of Ryland’s woman. Maybe the violet would signify the blossoming of my new start as my own woman.

I was not as good at dying my hair as Ryland had been—my fingers were clumsy, and it was a long, laborious process. When I had finally finished, I did not look in the mirror but leaned against the wallpaper and closed my eyes, willing myself not to sink into it. I was my own woman now—I had separated myself from the girl I had once been.

I looked down at myself, at my once-bright hair but all I could see was the blank white of my skin.

by Evelyn Lee Lucado

Good Grief

The Cat died, and the Dog won’t stop circling

the spot where she used to sleep,

that sunny spot by the back door.

The Dog settles with a huff on the woven rug

and stretches his limbs the way she used to do,

but not quite as graceful.

Sometimes I wonder if I was good enough,

could I write the Cat into immortality,

the same way I collect words

like green blotching bruises? The same way

I hold grief in my arms like a lover,

press kisses to their hair,

trace the shape of them with my fingers,

legs tangled in the sheets as the sun peeks

through the blinds, eyes closed—

pretending to sleep—bodies warm and weary

and bitten. I find myself praying

they don’t leave when they wake.

But the Dog doesn’t care for my metaphor.

I haven’t vacuumed the rug yet

It still smells like the Cat.

For now, that’s enough.

Skipping through Scarborough by Julianna Nelson-Gaudette

by Evan Iseli

The Same Schedule as the Stars

As Emmanuel careened down the highway, the distance between streetlights grew, to the point where it felt like he was jumping from one projected light swath to the next like they were lily pads. The bursts of darkness in between, inwhich he could not even make out the distinction of the sky, frightened him. It was the dead of night, and the road was monochrome under the glow of the moon—which was as harsh as the streetlights themselves. Despite the highway’s sterility, Emmanuel knew that it connected warm towns, brilliant cities, places that were the cocoons for people’s lives. Each car streaking by was simply a lone vessel in a tangible, more earthly cosmos, ushering time’s most important person to their next destination. The highway may as well have spanned different worlds.

Broad road signs rushed above Emmanuel and counted down to his exit. As he quit the highway, familiarityquietly set its hand upon his shoulder. The stark lights faded, and before he could blink tall stalks of grass and corn lined his vision and replaced the gray brick sound barriers. Reclaiming its bearing on the world, the cloudless night sky flourished above the farmland and promised to reveal even more of itself in the morning. Emmanuel could barely wait to see it from his family’s house, where he could step from the third floor balcony onto the flat ledge of the roof and see the earth divided into thirds: first the beach, then the sea, then the atmosphere.

He continued along the road and found that his memory was starting to kick in, so he switched off his GPS and followed the route that old routines had ingrained in his mind. His thoughts wandered back and forth through his life until they settled themselves fifteen years in the past. The present night may as well have been one of those nights from years ago, and now it surprised Emmanuel that his car didn’t smell like liquor. But the silence—the absence of voices and of music and of blaring wind passing through rolled-down windows—mounted until Emmanuel’s ears felt muffled, and he found himself hurtling forward fifteen years and reentering the current drive.

As he took the next exit, his entire body began to buzz with the distinct sensation that he was travelling in the right direction. He had something of a compass in his soul, and to him it was palpable that everything about this trip—from the job prospect to his familiar lodgings to the area itself—aligned with more divine notions of how his life should progress. His job interview at the health center was not for another week,but he wanted the time to settle back into a house and a town that he had not lived in since he was eighteen. His parents had bought the vacation home when he was a child, but it ended up being paraphernalia for a life that they were never living.

The only vacation that Emmanuel could remember was when his parents had flown across the country to attend to asupposed family emergency, yet had packed scuba diving gear and a beach umbrella. To his knowledge, the only person who had ever spent any significant time in the house was him.

As he drove down the last stretch of highway, he thought about the colossal bridge that was only a few miles from the house. It was a brutalist matrix of concrete slabs, yet it lit up at night, brilliantly, in red, white, and blue, theneon of its pillars reflecting off the blank sky and giving the effect of perpetual evening. Emmanuel wondered if it still bathed the shore in its glow.

The road on which he drove narrowed, and indeterminate wisps of light in the distance began to clarify and take shape. Fainter beams shot towards the sky, while more concentrated brilliance took the form of a bridge, its distinct columns and the baubles atop presiding over the highway and the sea. Emmanuel could also make out the silhouette of his home, which like a dormant sentinel watched him in turn. They exchanged a silent greeting when he approached the placid string of duplexes. The tires of Emmanuel’s car emitted a hollow crackle as they glided across the small parking lot, a sound that almost echoed, that tickled the stillness. When he disembarked, the air embraced him as it would an old friend, and on its stinging fall breath were traces of the past season.A thin but distinct layer of sand coated the lot, and the crisp edges of the homes scraped against the night.

Fifteen years ago, he had made this same drive in the haze of early summer. Emmanuel recalled standing in his parents’ driveway, prepared to blaze off to the shore, sifting through the last of the legal notices and letters that had been accumulating on the floor of his car for months. His mom had taken to piling them there so that she wouldn’t have to think about them. Or perhaps to somehow involve him, in hopes that he would become entangled and have no choice but to stay. And yet it had been her idea to send him to the vacation home while she and Emmanuel’s dad continued their arduous battles. For months his dad’s proclamations that Emmanuel’s mom was a liar and that everybody in the world knew it rang out through the house, assertions matched in ire only by the prosecutor in the courtroom as he set out to prove that Emmanuel’s mom had built her legal career on bribes and compromised evidence. Amidst the concurrent criminal trial and divorce proceedings, a teenage son had been too much to handle, so Emmanuel’s mom had slipped the key to the vacation home onto his key ring and told him to pack a suitcase.

It was the onset of summer when his parents had sent him away, and when Emmanuel had arrived at the beach years ago, the pang of his soul’s compass told him that his exile was provident. A fuzziness swept across the coast andobscured thought from the thinker, which in turn made it easier for Emmanuel to embrace the distance. He had spent the first week on the house’s balcony, staring out into the thick, granular air and forgetting that time was passing. One night he discovered that he could climb onto the roof, and spent most of his next week up there, observing the sea by day and the lit up bridge by night.

In the middle of the third week, he had remembered that his parents had a runabout moored to the dock behind the house, just beyond a belt of eclectic foliage. He took the boat out on the water, but it was difficult to maneuver amid the strong afternoon winds and choppy waves. Far from the shore and barely able to control the craft’s direction, he decided to sail it back in. He carefully retied it to the dock cleats, straining to fasten the knot as tight as he possibly could. Tense, he sat curled up on the dock, the wind roaring at his back. The runabout began to drift, tugging at the rope as if it wanted to sail off of its own accord, and Emmanuel hurriedly untied and retied the cleat hitch to secure itto the dock. Sensing the temptation of the horizon, he feared that the boat would meander on its way in search of something greater and strand him on the beach. He told himself that if he remoored the boat fifty times, this would not happen. And so, he untied and retied the knot fifty-one times, because he believed in good luck.

Now, he stood on the balcony and tried to make out the forms of the dock and the boat in the pitch-dark. Nestling his foot on top of the railing and in a corner where the exterior walls of the house met, Emmanuel hoisted himself onto the flat portion of the roof. Remembering the way he used to situate himself when he was younger, he sprawled out across the ledge and tucked his hands under his chin. Night warily approached morning, and the shingles were already dewy. From up on the roof, Emmanuel could see every shadow that the bridge cast with its radiant light. The bridge was on the same schedule as the stars, beaming to life when the sun set and powering down when the sun rose again.

Emmanuel slept until noon the next day, and when he groggily rolled out of bed his surroundings disoriented him:the soft walls engulfed in sunlight, the docile paintings tastefully arranged on the walls, the smell of an old, scented candle pervading. Taking a walk around the house, he noticed that in the light of day it appeared lived-in. The couch cushions were awry and had retained an imprint from someone sitting on them. The coffee table sat crooked and too far off to the side of the living room, and upon close inspection, the coasters on top of it had faint rings. Emmanuel, conscious not to fix the cushions, sat down on the couchand turned on the TV, finding that it was paused in the middle of a movie. He thought this curious, and began wandering about the rest of the house and searching for any other signs of life. He explored every room, looking throughdrawers and cabinets. When he opened the door to the fridge, a pungent smell wafted out, emanating from the host of bottles populating the shelves. Emmanuel noticed a small, shiny object lying inside and reached in for it—it was a bottle opener shoddily engraved with the name “Byron.”

Now Emmanuel was certain that his parents had not visited the house since his stay fifteen years ago. The memory of Byron bumbling about the room and boasting about his engraved bottle opener rushed back and made Emmanuel chuckle. A group of people—Emmanuel could not remember exactly who—had challenged Byron to try to open a beer with his bare hands, and Byron, never one to turn down a challenge, ended up slicing into his palm with the bottle cap by accident. Amidst the fray, hehad tossed his bottle opener into the fridge, where it was to remain for a decade and a half.

Each time Emmanuel stumbled across a stray item while exploring the house, he wondered if it was a relic from the constant stream of people that had come and gone from the home during that summer. Thinking back on it, he could not even hazard a guess as to how many people had frequented the place, and he certainly could not remember all of the names. He had met Byron a month into his stay, when Byron had been an ever-roving reveler. Ambitious and eager to get away from his controlling parents, Byron had left home as early as possible to pursue photography, thoughhad discovered a penchant for partying. He could not afford an apartment in the town and had been going between couch-surfing and sleeping in his car, so Emmanuel let him stay at his family’s vacation home in exchange for whatever rent Byron could pay, which was never much. Without warning, a bevy of the ever-charismatic Byron’s friends began showing up to the house en masse, drinking and hollering and phoning even more people. This continued for the rest of the summer.

Emmanuel collected all of the miscellaneous items left by his past guests and put them all in a cardboard box, before deciding to take each article out and put it back exactly where he had found it. He paced around the house for a good hour, making sure everything was in its proper place before the growls from his stomach got the better of him, and he decided to drive to a restaurant. Pulling away, he could see clearly the house in the rearview mirror and the bridge up ahead. As he crossed it inthe daylight, its thick beige facades seemed stark and unwieldy, and its sagging cables seemed a blight. Juxtaposed with the twinkling, ebbing water below, the bridge was an imposition, flat and lackluster compared to its nocturnal alter ego, which may as well have been the town’s nexus. To Emmanuel it was fascinating that something’s function and significance could change so drastically depending on which cosmic orb lit the sky.

The highway took him past long stretches of shore before depositing him in the heart of the town, where he found a parking spot and walked to the restaurant. Inside, it was dim and humid and loud, the punk rock blasting over the speakers keeping rhythm with the movement of patrons and waiters. Thebustle comforted him, and he eased over to a seat at the bar. He sat there for a few minutes fidgeting with a toothpick before the bartender finally made his way over. The man was about Emmanuel’s age, with a faint beard and a hardened face.

“What’ll it be, my friend?” the bartender asked. “Can I take a look at themenu?” Emmanuel replied.

The bartender gave a slight nod, then dashed off to the other end of the bar. On his way back with the menu, thebartender was stopped by another customer, who quipped something to him and made him guffaw. That same laugh had echoed through Emmanuel’s house years earlier, and there, under the faint lights and amidst the blaring music, Emmanuel recognized the bartender as one of Byron’s old friends. Clear as day, he could remember the man’s booming voice as he dared Byron to open a beer with his bare hands.

When the bartender returned with the menu, Emmanuel wagged a finger at him. “I used to know you,” he said matter-of-factly.

The bartender rocked his head back and grinned, wiping the inside of a glass with a towel as he spoke. “Oh yeah?” he replied.

“Across the bridge, that’s where my house is. Right near the shore. I think you used to hang out over there.”

The bartender cocked his head as if trying to remember. Finally, the memory sparked. “Yeah, oh yeah, okay,” he said, nodding.

“We used to pull our cars onto the beach and light fireworks,” Emmanuel said. More memories began to fall into place for the bartender. “Emmanuel, right?” Emmanuel smiled. “Yeah.”

Nodding for a moment, the bartender supplied, “Marvin.”

“Marvin, yes.”

Marvin excused himself to attend to something in the kitchen and disappeared.

Emmanuel tried to peruse the menu, but thoughts of the past occupied his mind. When Marvin returned, Emmanuel asked, “Does everybody still get together?”

“Not really, we’re all kind of busy these days,” he replied, chuckling. He glanced around. “You know, I like my job. I’m trying to hang onto it while I can. It’s turned out to be a pretty good thing.”

“I’ve got a job interview next week. At the medical center. I just finished my M.D.” Marvin raised his eyebrows. “You can do a lot with that.”

Emmanuel shrugged. “They don’t need any more general practitioners at the medical center right now, so I’ll start at a lower position.”

“Still, good money. Wish I had been able to do that.”

“It’s been fifteen years, but this place is pretty much just how I left it.”

Marvin turned his head. “The way someone put it to me recently was that the people here change more than thetown does.” He thought for a moment, then continued, “If the hospital isn’t offering the job you want, why did you come all the way down here to interview?”

Emmanuel began taking toothpicks from the plastic cup in front of him and laying them out on the countertop. “Itjust feels right, you know.” He arranged them in a continuous line, the end of one toothpick just barely brushing against the beginning of the next. “Whenever I see a compass,” he continued, “I always think of that feeling, you know, when something feels like it is as it should be.”

“Because a compass tells you where to go?”

“Yeah. I like to think of it as a compass in my soul. That’s what guides me.”

Marvin raised his eyebrows pensively. “I’ve never thought about what guides me.

Whatever it is, it’s different now, probably, then whatever was guiding me back when we used to know each other.”

Emmanuel wiped his hand across the bar and ruined his line of toothpicks, then began rebuilding it again.

Marvin continued, “I’m also not sure I believe in there being one set direction for my life. I like to think I have many roads before me.”

He looked at Emmanuel. “Emmanuel, think about all the other places you could get a job. With an M.D., you can go just about anywhere.”

Emmanuel simply nodded. The alarm on Marvin’s watch sounded, the shrill beep cutting through the noise of the restaurant.

“Emmanuel, it’s been great catching up with you. It was truly good to see you, my friend, but I’m going to have to cut things short. My shift just ended. I’m going home to see my kid.”

“It was good to see you, Marvin.”

Marvin straightened up a few things behind the bar, then departed with a curt wave. Emmanuel nodded back, then glanced back down and began destroying and rebuilding his toothpick line once again.

He returned to the house later that evening and grabbed a stale beer from the fridge. Slipping Byron’s bottle opener into his pocket, he meandered up the stairs and onto the balcony, waiting for the sun to set and for the bridge to light up with its red, white, and blue. The wind picked up and then calmed again, and the nearby pines oscillated in solidarity with the lapping, foaming tide. The deeper blue of afternoon paled to a gray as the day waned, and as the sun charted a course that would lead it below the horizon, the sky began to acquire a deep red. Emmanuel retrieved the bottleopener and lined it up with the cap. It popped off crisply but hit the deck almost silently.

The red of the sky became darker and darker until the atmosphere was a shadow above the sand and sea. Patient and stolid, Emmanuel waited for the bridge to ignite in neon. The wind subsided, bathing the night in silence, and with silence came stillness. The hours wore on, and the bridge remained as it was during the daylight hours: dormant. Emmanuel longed to see it light up one last time, because he knew he would be leaving in the early morning. Somewhere in the recesses of his soul lay the remains of a compass, and he would need the bridge’s light to guide him.

District Lamb by Julianna Nelson-Gaudette

by Melinda Kern

Handbook, for Pressing Flora

Go off on a little trot.

Greet them; be polite.

Then, take one, two,

More than a few,

Bring them home,

Place them in this book

Right here, to the right

Next to these words.

Place any weight atop

Flattened between pages

Lined with waxy paper.

Color mellows as life drains.

Dry and crisp, still soft petals.

Remove with tweezers or gentle fingers

Store in envelopes lining a shoebox.

Label all parcels,

Easy to find for later,

Frame them in an unnatural state

Between the glass.

They remind you,

Their life was not to be saved,

Kept, or prolonged.

Color lightens,

Distorts––ivory, yellows, and browns—

Corpses clearer over time.

You were never lost to me.

Your form never leaves,

Holds the same place

Little ghosts trapped.

There was never an illusion,

Preservation preserves only so long

Till you crumble or crack,

Fizzle away, to sprout anew.

Even then I wish to be there for you––

Return to the worms and pill bugs—

Please, never forget,

I intervened.

On the Chester River by Isabel McCreary

The Silent Choir by Jeremy Cress

by Solomon Bradley

A Talk with Anubis

After Raymond Carver and Bob Dylan

Did you get what you wanted

from this life?

I did.

And how do you think

the scales will settle?

My heart will snap the chain.

And why do you think so?

Tears break even the divine;

tears scrape through my veins.

And what will you do now,

my blue-eyed son?

I will shift the sands

and feed my tears to the dunes.

And what will you do next,

my darling young one?

I will cling to you

and walk home.

by Sarabeth Metzger

Hero

Everyone knew their dads. I guess it didn’t matter too much. I had another mom. But the thought always lingered. Who was my dad? He was like some mysterious figure in the back of what small number of baby photos we had of me. What could he have done that was so bad? No one would talk about him. He was a silent whisper among my older relatives. My sister and my brother looked like a swirl of our mother with a tad of their dad. I just look like Mom in the daylight: when I put my hair up in a clip, do my makeup like hers, or dress in maroon. It was such a reach to compare us, like a hopeful affirmation that one day my features would grow into hers.

One evening, on a particularly draining day, I got the courage to ask about my dad. My mom grew herself an attitude and started to tell me the painful memories that she’s kept hidden behind her stone-faced exterior. My poor mother had been broken and repaired all over again so, so many times. From hours and conversations and heavy acid tears, what I got was that my dad was a superhero.

He roamed alleys at night like a watch patrol. He hid behind trash cans, dumpsters and made his way to the deepest parts of the city. Dad preferred to remain in dangerous areas with high amounts of crime. He kept a small, tight group of friends, all with whimsical, varying names with elaborate stories behind them, carrying ambitiously positive titles. Ms. Sunny.

Mom said that in the past, when Dad would come home, beaten and battered with a bloody lip and bruised arms. He’d fall asleep standing up and sway from side to side. He stayed up too late fighting crime. He’d consistently sneak away just to come back worse than before. From what I could gather, he didn’t enjoy his job.

His eyes got clammy after a fight because he’d taken on more than he could handle. They’d carry words he was unable to say, and instead of speaking, he’d cry out his inner conflict. He wore his heart on his sleeve, and his arm received too many punches. He was wounded, shaking, cold, and always went back for more. It sounded noble.

My mom emphasized that he would lie a lot and put others at risk. But did Superman not originally lie to Lois Lane? There are patterns to this! Of course, he had to keep secrets; he had a secret identity! I can imagine he was doing it for the greater good, and my mom was being selfish.

Inevitably, every hero falls.

Dad lost the superhero base in a game of war, defending his honor. I still honored him. Bruce Wayne is still Batman without the Bat Cave.

Dad always canceled plans and left me waiting on the curb. I’m sure something came up, a battle, or he’s practicing shooting, like Mom said. It wasn’t a place for a kid anyway. Dad would save me.

I told everyone at school about my dad’s great feats. I finally had someone to talk to like the way the other students talked about their dads. It was a way to relate to and excite my peers. How could they try to compare their dentist father to my superhero dad?

But no one believed me.

That’s when the teachers called home, and my mom explained.

Heroin.

Not Hero.

by Melinda Kern

Between Two Deaths

I don’t think I will survive this change.

She will: the one that bursts out of my skin.

She’s broken out,

Ripping the boundary—

It was a nasty fight to get out; blood-film hugs her.

If the egg hadn’t softened, she would have drowned.

Rotten inside a babbling stubborn shell

Backlash in infection.

Stop to eat the viscera of the egg, the last remnants.

Leaving her birth behind to face the strife she was summoned for.

There is no time to grieve a vessel of what she once was,

The clone marches on.

Her emergence doesn’t insult me, who she replaces,

No backstabbing here.

She’ll go one-mindedly forward on my behalf,

Even if, one day, it means a death for her too.

Draco Mortem by Jeremy Cress